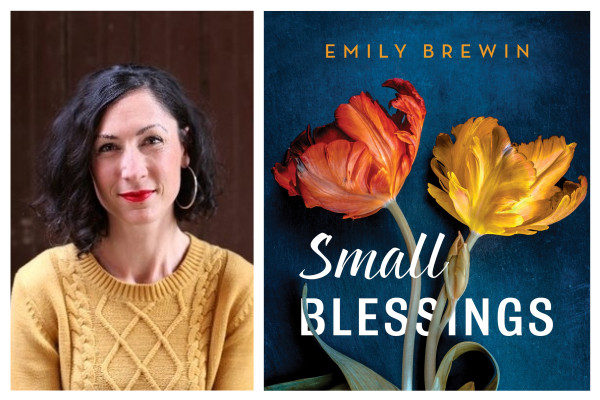

Small Blessings, by Emily Brewin, Allen and Unwin, rrp $29.99

Small Blessings, by Emily Brewin, Allen and Unwin, rrp $29.99

Reviewed by Joe Blake

Once again we ask you to raise your metaphorical hat to Joe Blake. Not content with preparing his fire plan, polishing his “are you safe?” terrorist alert fridge magnet and preparing his submission to be the next leader of the Merton CFA splinter group fire brigade, he’s got us into another book review. And this one is a corker!.

As a consequence we’ve had to put on hold the esteemed bio from Alan Myers QC, “How I became Chancellor” till next week, and hope that none of our readership are discontented now they have their exclusive set of autographed board games as covered in last weeks thrilling instalment.

Now, over to you Joe, (he begins)………

Once upon a time, the notion of class was always close to the surface in this country. The inequalities in society were recognised as part of its structure, not just the fault of the individual. Because of this awareness, social welfare payments – the dole, old-age pension, single parent payments – were set at a level so recipients could survive. No money was given to private schools. The list goes on. Class consciousness was everywhere. Working class parents worried about their kids getting an education, on two fronts: (a) would it be enough to allow their grownup kids to relate to people above them in social ranks; and (b) would these kids lose contact with their families and the peers of their childhood?

These days, that thinking has changed and the meanness of the Howard years prevails. Blaming the victim has become a new national sport, and lauding those who’ve enriched themselves (usually by cheating) is the new norm. When, in a recent interview with a Murdoch journalist, Tim Winton mentioned the concept of class, the response he got made him feel “as if I’d shat in the municipal pool.” Luckily for us, Emily Brewin hasn’t received the memo about the uncomfortable c-word, and she’s produced a wonderful novel to prove it.

Rosie, a former drug addict, is a single mum to Petey, who’s maybe 8 years old and high-functioning autistic. He’s a lovely kid, but his obsessions sometimes lead to tantrums. Determined to make sure he gets a better childhood than the miserable one she suffered, she’s studying year 12 at TAFE, with maybe uni to follow. In the meantime, the going is tough, living in a tiny inner-city commission flat and working in the supermarket underneath to get enough to live on. If you’ve ever been to those flats you’ll know it’s no fun: privacy doesn’t exist; a bad neighbour is multiplied by 150. It’s easy to lose your mojo here. Added to that, a new problem rears its ugly head. Her ex, the junkie who continually bashed her and sent her out on the streets so he can score, has just got out of prison and is stalking her. Eventually the pressure builds up so much she explodes, and Petey runs away and can’t be found.

Isobel, the other main character, has a different story to tell about class. She grew up in heavily-polluted Altona, where Dad worked in the refinery and Mum threaded plastic cables all day. Mum knows how bad it is to be poor, and she’s dead set on her kids getting the best education she can pay for, even if her hands are destroyed by all the extra work hours needed to get the money. Isobel is very bright, but she never fits in to her elite girls’ school; she’s just not rich enough. Despite (or because of?) not fitting in, she duxes the school, and enters Law at Melbourne Uni. While there, she meets (and marries) a man from Toorak, and life is looking up. They’re both ambitious, and sacrifice a lot for their careers; she even gets to be a partner in her prestigious firm. One day, though, she decides it time to become a mum, and goes into IVF. Coincidentally, everything at that time starts to fall apart. Her mum, who embarrassed her mightily in front of her snooty school companions, is about to die. Her husband becomes distant; it rolls on and on.

Towards the end of this wonderful book, Rosie and Isobel meet up, and, despite the odds, become friends. I won’t tell you about all the twists and turns, but it’s a great story, filled with perceptions and insights that show a hell of a lot of lived experience or some brilliant research. There are so many little details here.

This is Emily Brewin’s second novel, and let’s hope there are plenty more to come. Her debut was brilliant; this is even better. How far can she go?