Just to let you know there’s more to the north of Kalkallo than the genius of the Murray Darling Basin Plan, clean coal and the certainty of Franking Credits as the singular greatest initiative of the century. From our sage of the near north comes proof that in some places, uncorrupted by consumerism and corona virus people still READ BOOKS!

Just to let you know there’s more to the north of Kalkallo than the genius of the Murray Darling Basin Plan, clean coal and the certainty of Franking Credits as the singular greatest initiative of the century. From our sage of the near north comes proof that in some places, uncorrupted by consumerism and corona virus people still READ BOOKS!

That’s it folks, they can be found with the telly off, the I-pad discarded and the mobile muted, actively engaged in the act of reading. This phenomena could spread, and like coronavirus, the Federal Gover nment has no idea how to tackle the insidious creep of thought and ideas. So stand with us, and breathe deeply as we read this scintillating review from Joe Blake. Once again, he has transformed his styli into a hammer, and nailed it.

nment has no idea how to tackle the insidious creep of thought and ideas. So stand with us, and breathe deeply as we read this scintillating review from Joe Blake. Once again, he has transformed his styli into a hammer, and nailed it.

We dedicate this review to Sergeant Tanner of the near north who clearly knows how to make the system work. And if you don’t believe us just ask Lawyer X.

Take it away Joe:

Bowraville, by Dan Box, Penguin Viking, rrp $34.99

Reviewed by Joe Blake

You don’t need to be Einstein to know that Aboriginal people get a raw deal in this country. There’s all sorts of statistics about life expectancy, incarceration rates, school retention age … the list goes on. They’re all general; this book talks about the horrifying particular.

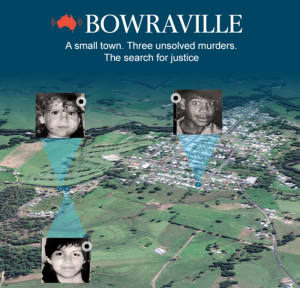

The small town of Bowraville sits somewhere near the north coast of NSW; its 1000-head population is about one quarter aboriginal. Nearly 30 years ago, three Aboriginal children were murdered there in the space of about five months. Despite an ongoing campaign by their families from 1991 to the present day, no-one has ever been convicted of those crimes. This outstanding book points to one overriding cause for the lack of convictions: white Australia just doesn’t care enough. It’s almost like: “Well, they’re only blackfellas, so why should we bother investigating properly?”

The initial reaction when each of these kids disappeared was predictable: they must have gone “walkabout”. If they’re Aboriginal, they’re not really a missing person until they’re proven dead. Even when the bodies of two of them were found, and the clothes of the third, the cases were not considered to be related, despite all three being last seen in houses in the same street.

There are other glorious legends at Bowraville. That symbolise and celebrate something way more profound in the making of Australia GRATE!

Local police worked incredibly hard to try to solve these crimes, but the official attitude of their superiors was woeful. Most murder cases have a posse of detectives assigned to them, and the best technology the force can muster. For Bowraville, it was three part-time officers with some butcher’s paper and a few textas.

Like most white people who are lucky enough to spend time with indigenous Australians, the cops soon came to love the community they worked with. They got beneath the veneer of mutual misunderstanding, and dedicated themselves to the fight for justice. Everybody involved believed they knew who did it, but the lack of resources, combined with lack of interest further up the justice scale, meant nothing was ever resolved. The community showed incredible resolve and staying power over 27 years, even at one stage forcing the government to change the law of double jeopardy (you can’t get tried twice for the same crime), but all to no avail.

Journalist Dan Box came late to the scene of these crimes, at the request of the tenacious cop who’d been chasing a conviction for 20 years. He wrote a series of articles in the Australian, and produced a number of podcasts which gathered a huge following. The main suspect for all three murders, who had maintained his silence after his acquittal for one of the murders, even agreed to be interviewed in one of his podcasts. He joined in the community’s campaign to hold a retrial. In the end, nothing happened, probably because the initial investigation and court case were so badly bungled.

If you’re looking for an uplifting read, this book is certainly not for you. If, however, you want some indepth understanding of what’s causing all those depressing statistics mentioned earlier, you’ve come to exactly the right place.