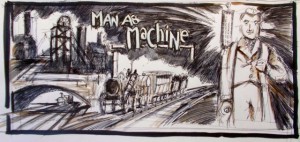

Previously, in Man as Machine, Tarquin O’Flaherty postulated “. . . business was beginning to sniff around for alternatives to the exploitative monopolies of river and canal commercial transport. This interest would turn the world upside down.” Here he continues his engrossing account of Robert Stephenson’s influence in the world of steam power, and trains.

With the exception of the Duke of Wellington, an Irishman, who had defeated Napoleon’s Grand Armee at Waterloo, in Belgium, (1815) the most popular man in England, at this time was undoubtedly the scientist, Sir Humphrey Davy. He had the happy knack of discovering or inventing things that were immediately useful. He made all sorts of discoveries regarding agricultural fertilisers, and in his lifetime had discovered chlorine which was immediately used as a superior bleaching agent in the textile industry. He also came up with potassium, magnesium and sodium amongst others, all of which were also put to immediate use. This made him a remarkably popular scientist. He became quite wealthy, and received heaps of honours including, in 1820, becoming President of the Royal Society. He was an important man.

With the expansion of the coal industry, working below ground was becoming increasingly dangerous. Coal harbours highly volatile gases and carrying naked flames into the Stygian depths was fraught with peril. The mine where Stephenson worked, Killingworth, had killed ten men in 1806, and twelve more in 1809. This horror was being repeated wherever there were coal mines, culminating in the 1812 explosion at a Gateshead colliery which killed 90 men and boys. Something needed to be done. Sir Humphrey Davy was called in, pondered the problem, and came up with the Davy Safety Lamp. The nation was grateful and the lamp was adopted everywhere, except in the North East.

In the North East George Stephenson had already invented a safety lamp which could be taken below ground without fear of endangering lives. It was ‘Geordie’s lamp’ or George Stephenson’s lamp and was championed in the NE coalmines ahead of Sir Humphrey’s version.

Well, there was hell to pay, and Sir Humphrey took frightful umbrage. There was much pompous huffing and puffing but, in the end, it was shown that Stephenson had been experimenting with his safety lamp long before Davy arrived in the North East. Davy, accepting none of this, to his dying day insisted that an uncouth person of Stephenson’s calibre couldn’t possibly have come up with something as sophisticated as the lamp. Influential people disagreed heartily with Davy and more or less told him to pull his head in. And that was that.

Incidentally, people from the North East of England are, to this day, still referred to as “Geordies’, in memory of those supporters and defiant users of ‘Geordie’s’ lamp rather than the Davy version.

Stephenson’s teenage son Robert, still apprenticed to George’s old friend Nicholas Wood, the manager of Killingworth colliery, was withdrawn from there to help his father survey the ground for the Stockton-Darlington railway. Already he showed the same natural aptitude for engineering as his father, with the singular advantage of a first class engineering education. In 1822, still only nineteen, Robert was invited to join William James, a nationally well regarded and enthusiastic promoter of railways, to help with the first survey of a proposed line between Liverpool and Manchester.

Whilst this survey is being undertaken, Stephenson senior was appointed as engineer in charge of the building of the Stockton-Darlington railway. At roughly the same time he had fallen out with his friend William Losh. It will be remembered that Stephenson and Losh had entered into a partnership to manufacture patented cast-iron rails which were much in demand for use in the collieries. However, in 1821 Stephenson had heard of, and gone to see an engineer called John Birkinshaw, in the town of Bedlington. Birkinshaw had perfected a method of producing wrought (or malleable) iron rails which were infinitely more flexible and much less prone to failure than the cast iron type. Stephenson, recognizing their superiority, was immediately won over, and insisted on using them on the Stockton and Darlington project. This is a typical instance of Stephenson’s absolute commitment to continued improvement in all aspects of railed transport. He was earning good money from his patented cast-iron rails, yet he was immediately prepared to forego this in order to make way for this new advance. Stephenson could see the future, and he knew it was trains. William Losh was not impressed.