George Stephenson has managed to put his partner William Losh off-side by favouring a competitors wrought iron rails to Lush’s cast rails. Tarquin O’Flaherty continues his story.

Such was the animosity generated at the Losh Ironworks by this sudden switch to the new rails and the consequent loss of business that Losh and Stephenson didn’t speak to each other for years, and when Stephenson did need cast-iron rails he had to go much further afield, to Wales, to get them.

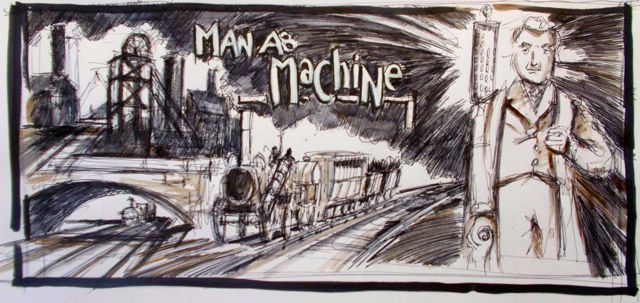

Something should be understood here of the makeup and character of George Stephenson. His behaviour towards William Losh was not an abberation. Time and time again, people whom he no longer deemed useful, people who had gone out of their way to help him in the past, he simply turned his back on. Stephenson knew what he wanted, was ruthless in obtaining it, and did not suffer fools. Though a brilliant, self taught engineer he was nevertheless, a rough diamond, constantly coming up against smoother, ‘middle-class’ individuals who tended perhaps, to patronise him, particularly as he maintained both his broad, almost impenetrable ‘Geordie’ accent, and his brusque mode of ‘plain speaking’. To discover that these intimidating ‘smoothies’, his supposed superiors, understood much less of engineering(and the world in general) than he himself did, must have been particularly galling. He had, by providing Robert with a sound education ensured his son’s ascendancy, his position in society, something, with his own background, he could never have achieved for himself. He was delighted and inordinately proud when in 1822 Robert obtained a six month placing at Edinburgh University.

Time passed and the Stockton-Darlington line was successfully forging ahead. Robert had returned from the Liverpool-Manchester survey and had worked with his father on many projects, including the Darlington line, and the initial parliamentary lobbying in London. It is significant to note here that during this time, father and son, backed by the Quaker Edward Pease, and joined by Michael Longridge, the owner of the Bedlington Ironworks (producer of the wrought iron rails) formed their own company to manufacture their own locomotives. Remarkably, the young 19 year old Robert was made managing director and entrusted with the job of setting the manufactory up, taking on suitable staff and preparing the ground for the building of two locomotives which his father had ordered for the Darlington line. The business, set up at Forth Street, Newcastle, was called The Robert Stephenson Company. The locomotives were to be called the ‘Locomotion’ and the ‘Hope’.

In 1824, at the grand opening of the Stockton-Darlington line, many new and interested groups attended representing other proposed new railways, including the Liverpool-Manchester and the Leeds-Hull, amongst others. A greater interest in railways, if not yet direct investment,was becoming more widespread. The only person who was noticeably absent from this grand affair was young Robert Stephenson. This remarkable young man, too long in the shadow of his father, had struck out on his own. He had taken ship to South America.

For many years, tales of Cortez, Montezuma and the Aztecs, spectacular riches and gold and silver for the taking had circulated freely round the Empire and had inspired more than one expedition to the New World. Ten years earlier, in about 1814, Richard Trevithick, that inspired but wayward locomotive inventor, had joined one such expedition to the New World and had been waved off with great pomp and fanfare. He went there to introduce his revolutionary railway system to a breathlessly awaiting world, a system which would undoubtedly play a major part in helping to first mine and then haul out fabulous riches from this too generous South American earth. The reality,as Robert later found, was very different.

TO BE CONTINUED