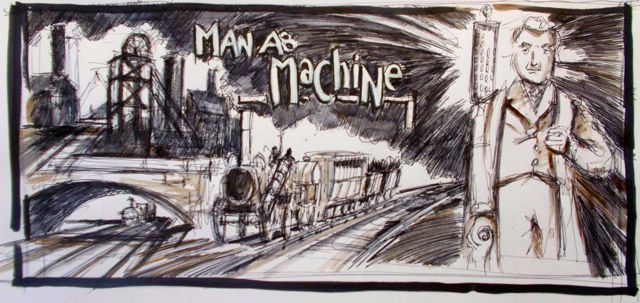

More on George Stephenson by Tarquin O’Flaherty

It is extraordinary how, in the first half of the 19th century, the reputable, and entirely respectable British engineering establishment set itself against George Stephenson. Stephenson lacked polish. He also had an almost impenetrable ‘Geordie’ accent and no recognised engineering qualifications whatever. He was also inclined on occasion to behave in a less than deferential way towards respectable engineers whom he considered to be incompetents.

Stephenson unfortunately possessed one other quality which the establishment simply could neither accept or forgive; this was, of course his embarrassing habit of solving problems other engineers had dismissed as wholly intractable. This was absolutely intolerable. The Rainhill trials seemed the perfect opportunity to put this coarse upstart in his place.

One of the most popular and widely read journals of the day was the ‘Mechanics’ Magazine’ which was, if not the official organ of the engineering establishment, then it was closely associated with it. The reporter on the day had the following to say:

‘The engine which made the first trial was the Rocket…it is a large and strongly built engine, and went with a velocity which as long as the spectators had nothing to contrast it with, they thought surprising enough. It drew a weight of twelve tons, nine cwt. at the rate of ten miles, four chains in an hour (just exceeding the stipulated maximum) and when the weights were detached from it, went at a speed of about 18 miles per hour. The faults… were a great inequality in its velocity and only…a partial [ability] to consume its own smoke’.

What this reportage fails to do is honestly acknowledge that the Rocket had fulfilled every condition of the test, both loaded and unloaded, without any mishap whatever. It is interesting and curious to note that there is an ungenerous, pinched and carping quality in this journalist’s ‘Rocket’ writing which occurs nowhere else.

By contrast, this same reporter goes into raptures of delight in his reporting on the performance of the ‘Novelty’:

‘…the great lightness of the engine…its beautiful workmanship…universal admiration…its truly marvellous performances…’

‘It was resolved to try first her speed merely…almost at once it darts off at the amazing velocity of 28 miles an hour…’

‘…It was now proposed to make a trial of the ‘Novelty’ with three times its weight attached to it; but through some inattention to the supply of water and coke, a great delay…[made it necessary to] defer the prosecution of the trial to the following day…’

The magazine, with barely concealed bias, is unfairly comparing an unloaded “Novelty’ ‘…darting off… ’ at 28 mph, with a fully loaded ‘Rocket’ hauling its stipulated tonnage along the set course.

The Novelty, ‘…through some inattention to the supply of water and coke…’ could not perform the weight-pulling part of the test the next morning, or any part of that day. In fact it did not recover ‘…its marvellous performance…’ until the following Saturday where it managed to travel for three miles before damaging one of its steam pipes and coming to a halt. Nevertheless, despite these problems, the ‘Novelty’, simply by its appearance, was a real crowd pleaser and most of the spectators wanted it to win. By comparison, the Rocket was a behemoth, huge, unattractive and smelly.

To Be Continued (TOMORROW – HOPEFULLY)