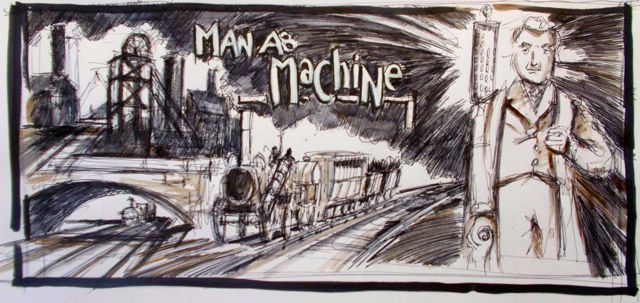

Previously in Man as Machine when “(s)omewhere in Cornwall the steering mechanism collapsed, the locomotive took off, out of control and crashed heavily into a house” we left the party ensconced in a public house whilst both locomotive and house were destroyed. Let Tarquin O’Flaherty continue his account of George Stephenson

The year 1804 was a milestone in the development of Trevithick’s steam locomotive. Challenged in the South Wales collieries, where he was supplying stationary engines, to use his engine (on rails) to haul 10 tons of iron for nine miles, he not only did this but included seventy men in the load as well!

The great difficulty with all this was both the weight of the engine and the vibration. Time and time again the wooden rails were chewed up and spat out. Even when later cast iron rails were used the engine’s great weight cracked and split the brittle rails. Some of these problems seemed insurmountable.

Whilst all of this astonishing development was going on, George Stephenson was growing up. Aware of the value of education, he paid for private lessons in reading, writing and arithmetic. Working in the coal mines in the North East of England he found he had a natural understanding of machinery and was soon put in charge of maintaining most of the mine’s stationary steam engines. The Wylam colliery, having heard of the Trevithick engine, ordered one to be built at Gateshead in 1805. The engine worked well enough but it was found to be impractical because it wrecked the railway tracks. It never left the testing ground at Gateshead. Cosidering how much excitement and interest this must have generated locally, it seems inconceivable that Stephenson would not have been aware of it.

Trevithick, in 1808, put together a new locomotive and exhibited it on a circular railway track in London, charging admission. Sadly, even the new improved engine eventually destroyed the track. With this, Trevithick, an astonishingly inventive engineer, abandoned the idea and moved on to other things.

As is usual in these matters, for the next few years, interest in locomotives waxed and waned as people kept on coming up against the same old problems. Gears, wheels, and axles were all very imprecisely manufactured, which was perfectly acceptable for slow moving, horse drawn machinery, but applying this standard to faster engines inevitably resulted in bone shaking vibration whenever a little speed was demanded. This vibration literally caused machinery to fall to pieces.

George Stephenson, by 1814 was 33 yrs old, with a young son, Robert, aged 11. His wife Frances had died of tuberculosis in 1804 having produced a baby girl who only lived for a few weeks. He was now employed as enginewright by a group of Quaker mine owners known as the Grand Allies. This meant that Stephenson was now in charge of all engine work for this group. Other mine owners had experimented with building locomotives and the Allies offered George the same opportunity. Stephenson had no education, was almost illiterate and was virtually a self taught engineer. He was also highly opinionated and arrogant. Engineers of the day scoffed at this ill bred upstart and openly declared he would come to nothing.