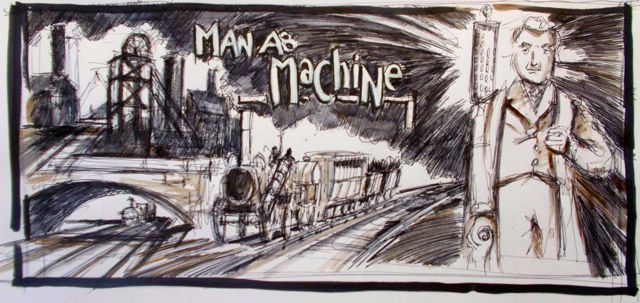

“Professional” engineers poured scorn on Stephenson for his ill-educated ways saying he would ‘come to nothing’. Stephenson counters with the superb design of an effective locomotive. By Tarquin O’Flaherty

Instead of coming to nothing he produced his first locomotive, the ‘Blucher’ in this same year, 1814. The Blucher had many faults, was forever breaking down, but each time it did, George was there to repair, modify or change whatever needed attention. The big problem with early locomotives was their lack of power. One of George’s great innovations was his routing of the steam exhaust into the chimney effectively creating what became known as a ‘blastpipe’. This increased the power of the engine so well that other engineers waspishly claimed that Stephenson had stolen the idea from some unknown but better educated engineer, whilst others claimed he had discovered the process by accident, by a fluke, and not by any educated process of deductive reasoning.

Stephenson ignored them and went on altering and improving the ‘Blucher’ adding external connecting rods to the wheels which dispensed with trains of gears, which considerably reduced vibration. He improving the system of valves which controlled the water and steam, and entering into business arrangements with a Newcastle ironworks owner William Losh, to improve the quality of cast-iron rails. Over the next five or six years he produced perhaps sixteen engines, each one new and improved, mostly for local colliery use, but with at least one going to Scotland.

In 1819 Stephenson laid down the first real colliery railway at Hetton, near Newcastle. It ran for eight miles with a mixture of stationary engines, gravity and locomotives. It was specifically designed to carry coal. From 1814, when Stephenson began work on the ‘Blucher’, most engineers had given up on locomotives. There’s no evidence that anyone other than George Stephenson was still working on locomotives in the period from 1814 to 1820’s.

Despite the ridicule of the profession, who haughtily considered locomotives (and Stephenson) to be a professional waste of time, Stephenson was beginning to acquire quite a reputation as an engineer himself, much to the chagrin of the London based engineers professional body. People began to arrive on his doorstep from America, France, Spain and Russia to ,look at his engines and learn.

Meanwhile, as the 1820s progressed, public interest in railways at last began to began to pick up. A Mr Edward Pease, a cotton merchant from Darlington, met George Stephenson to discuss the most economic way of getting coal from the inland Stockton mines out to the river Tyne, and thence to London. Mr Pease could see there was a quid to be made from lowering the cost of transport and was keen for Stephenson to have a look at the problem. Engineers had been consulted and a canal had been recommended. Others had suggested rail and stationary steam engines to drag the wagons along. Stephenson wanted locomotives. Pease wanted to invest in both a railway and George Stephenson. He could see there was money to be made.

The Stockton-Darlington railway was built and opened with great hoohah and fanfare and was hugely successful. It did wonderful things for Stephenson’s reputation. Nevertheless, the whole caboodle, from start to finish, was still regarded as a piece of smelly, noisy equipment associated with coal mines. Nobody, except George Stephenson perhaps, saw any other use than coal haulage for these great puffing, stinking monstrosities. Transport, in most peoples’s minds was still firmly fixed on coaches and carts, canal barges, towpaths and horses. But business was beginning to sniff around for alternatives to the exploitative monopolies of river and canal commercial transport. This interest would turn the world upside down.

TO BE CONTINUED.