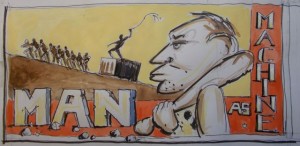

Man as Machine VII

Man as Machine VII

by TARQUIN O’FLAHERTY

Should you be seized with the desire to abandon urban hedonism in favour of the bucolic form, I would commend to you William Cobbett’s ‘Cottage Economy’.

In the late 18th century Cobbett, ‘perhaps the most powerful political pamphleteer in English history…’* made two forgivable miscalculations; in the first case, he wrote a pamphlet so inflammatory that warrants were issued for his arrest. His second mistake was to choose France as a place of refuge from the fuzz. Inconveniently, he discovered the French Revolution to be in progress. Cobbett made a good leg, his excuses and a bee line for America.

The Napoleonic Wars created such a demand for wheat that by 1814, prices had doubled and tripled since the early seventeen-nineties. During this period, in order to grow more wheat and make more money, enclosures accelerated at an astonishing rate. When hostilities ended, though markets collapsed and unemployment jumped, prices tended to remain unrealistically high largely because the markets were reluctant to relinquish their wartime profit margins. The resulting recession left the now landless peasantry destitute.

Cobbett hated London and what its industrialisation was doing to what had been a relatively self-sufficient peasantry. Admittedly Cobbett, an 18th century man, had a rather retro and romantic idea of country life, one of cottagers and squires, of continuity and self-reliance, of life going along unchanged. He was nevertheless absolutely focused on the injustices being heaped on the heads of a people who were beginning to be regarded less as human beings and more as simple machinery to be used until worn out, then simply slung on the scrap heap. Depriving people of access to land deprives them of their independence, of their ability to provide themselves with food, and leaves them wholly at the mercy of exploitative employers. Cobbett, like Arthur Young, wanted to ensure this didn’t happen. He wanted, and saw it as a right, that every peasant family should have a house, and sufficient land to grow enough vegetables and meat so that they might never go hungry. This would naturally involve diligence, thrift and hard work, but these were Christian virtues, good for the soul and would build up ‘Brownie’ points in Heaven.

As an illustration of Cobbett’s no nonsense approach, here (gloriously) is what he has to say about the business of drinking tea;

“…I view the tea drinking as a destroyer of health, an enfeebler of the frame, an engenderer of effeminacy and laziness, a debaucher of youth, and a maker of misery in old age…”(Cottage Economy.)

Beer is the stuff Cobbett’s cottagers obviously ought to be drinking and certainly not all this sugared, ‘sweet and saucered ceremonial’ that lifts so many little fingers in ‘Pride and Prejudice’.

Cobbett’s ‘back to the land’ approach differed greatly from that of the other great reformer, Robert Owen.

Robert Owen, at the age of twenty, was already owner of one of the most important cotton mills in Lancashire. He had bought the New Lanark mill in 1800 and immediately set about demonstrating that excellent profits could still be made without working the staff to death. It was generally held, amongst mill owners of the time that being at the bottom of the work chain was a law of nature and people occupying that position deserved all they got. Owen provided better wages, schools, education, good housing, sanitation and reduced the working hours considerably. He created villages with good roads, recreation areas and provided goods at cost price in the shops he built. His ‘Model Factory’ became famous far outside England, and drew lots of curious international visitors.

Cobbett on the other hand wanted to go back to a pre-industrial Britain where stout yeomen feared God, worked hard, and knew their self-sufficient place. He thought this infinitely preferable to the all consuming souless rapacity of the new industrialism.

Owen’s eyes were on the future, and he instinctively knew that industrialisation was unstoppable, and that factory production is not worth tuppence without a loyal and enthusiastic workforce. He knew the value of labour and respected it. He had no illusions whatever as to who or what was making him rich.

TO BE CONTINUED.

* “London; the Biography” by Peter Ackroyd

Pingback: Man as Machine XII | pcbycp