In England, before the Industrial Revolution, the common people were used by the aristocracy as both cannon fodder and labour. In return the common people used the aristocracy to provide them with food, shelter and work. There was a recognition that neither could exist without the other. The labourer needed the work; the farming upper crust needed the worker. Individuals acquired skills, carpentry, blacksmithing, farm husbandry and a host of other trades absolutely vital to the pre-industrial way of life. These were skills (and jobs) which could be passed on from father to son in a world which was constant and unchanging. There was an interdependence, a very real sense of knowing one’s place in the world, of certainty, of permanence, and no real sense of us versus them. With industrialisation and the rise of the ‘middle’ class, it rapidly became us versus us.

In England, in the aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, (early nineteenth C) the demand for wheat plummeted and millions of displaced working people faced starvation. Despite this, the British industrial system was in an enviable position. England had not been overrun by Bonaparte’s Grand Armee, and it had a vast pool of surplus labour. Europe, from the French coast to Deepest Russia had had it’s infrastructure devastated by Napoleon’s ambition. It would take a long time to recover

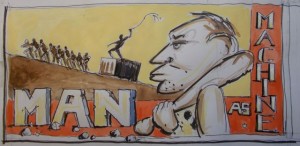

Robert Owen believed that an unemployed and impoverished class would reject his ideas initially and would therefore need to be ‘educated’ if his essentially philanthropic ideas were to be accepted. After all, he was trying to point out to them their own importance, the absolutely essential nature of their contribution to society, and that without them there wouldn’t be an Industrial Revolution. To achieve his ends he approached the rich, the ruling class to help him implement his ideas and bring about his vision for society. What must be remembered here is that Owen, in the Age of Reason, and by ‘cogito ergo sum’ reasoning, discovered that treating your employees well actually increased production markedly. Owen was initially very successful in getting this point across. Influential people listened to him, but only because of his success as an industrialist. To begin to treat employees as anything other than as an expendable commodity was unthinkable, absolutely unheard of, and smacked of ‘The World Turned Upside Down’, a reversal of the traditional Master/servant relationship. This, despite the fact that almost all mill owners at the time were drawn from the working class themselves.

Basically, Owen was preaching Socialism. Owen knew that nothing could be achieved in any industrial situation without workers. It followed therefore that the most important people in any factory, were the work force. Their importance in Owen’s view could not be overstated and their remuneration should reflect this. This was tantamount to suggesting that the workers were at least as important as the owners and that they should share in the profits. Industrialists were horrified and support for Owen’s Utopian ideas either faded away or were diluted to the point where they became unrecognisable. Clearly Reason, in the much touted Age of Reason, had it’s limits, especially when it interfered with an employer’s right to exploit his workforce by paying them starvation wages.

TO BE CONTINUED