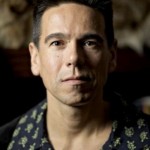

Professor Taiaiake Alfred, Founding Director of the Indigenous Governance Program at the University of British Columbia, Canada. This is an edited transcript of a speech delivered as The Narrm Oration, University of Melbourne 28 November 213

Professor Taiaiake Alfred, Founding Director of the Indigenous Governance Program at the University of British Columbia, Canada. This is an edited transcript of a speech delivered as The Narrm Oration, University of Melbourne 28 November 213

One of the central questions for all of us who live in countries with colonial histories and a colonial presence is how to transcend the relationships that have gone into forming the societies that we have inherited.

How do we transcend the histories of racism, dispossession and injustice as opposed to just the relationships that we all hope to have in the countries we inhabit?

Colonisation is seen as something of a historical period. People think of colonisation as a time in the past when ancestors from Europe came and did things, both positive and negative, that resulted in the formation of the societies that we call Canada, the United States, Latin American countries, and Australia.

People think about colonisation in terms of european peoples coming and with a pioneering spirit getting a foothold in the continent and putting the work into developing these societies, which are now paying off in terms of the prosperity and the level of comfortable lives that such people have today.

People think about colonisation in the past, and it’s true that it’s an historic period and it’s an historical phenomenon. From the 1500’s onwards [in Canada] people came from Europe and in effect dispossessed the indigenous peoples. People came and imposed belief systems and imposed ways of being. They came with the intent of imposing their own law and their own sovereignty on this area of the world that we call Canada and the United States. Those things happened.

But the problem in using this framework of colonisation as a framework for resolving issues and for understanding issues today and for making arguments today, is when people imagine that it is a strictly historical concept.

It’s a problem if people imagine that because now there are indigenous people in universities, that we speak English, that we’re Christian or post-Christian, that we drive cars, and have houses that are single family dwellings that resemble everyone else’s, that colonisation is in the past.

This is a fundamental problem for us who are still living with the legacy of colonisation in terms of the fact that our land was dispossessed, our belief systems and our cultures were disrupted, our families were dispersed and all of the other things that people associate with that historic era.

If colonisation was the intent to take land away, to impose foreign laws and to disrupt culture, if that would define colonisation in the year 1609 it pretty much defines the relationship today.

Therefore colonisation is not a historical reality but it’s a contemporary political, social, cultural and psychological framework for the relationship between indigenous peoples and non-indigenous peoples in countries like Canada.

In fact we’re not in a post-colonial society, we’re in a contemporary colonial society which the settlers have redefined in such a way that releases the burden of colonial guilt, by creating new words, new frameworks, new understandings that create a legitimacy for not only their presence on the land, but also for the things that happened in relation to culture, for the kind of privileges that they claim in relation to native people and the land.

And our society does this without acknowledging that today these processes are just as vital, just as ongoing, just as harmful and just as present in the lives of the indigenous population as they were in the 1600’s.

The fundamental problem is the fact that these societies are built on an ongoing re-colonisation of peoples that allows these societies to enjoy the privileges and the proserity that non-indigenous people have, and admittedly some of us indigenous people enjoy as well.

If we’re not looking at the dispossession, the continual occupation and the separation of indigenous peoples from the fundamental essence of who they are, we have a massive engine generating social, cultural and psychic discord.

It leads to more and more problems that need to be addressed by institutions of the society, and tragically the institutions are finding themselves unable to keep up the the issues that indigenous people are living, because that engine is rolling.

That engine is continuing to produce discord and harm, continuing to produce psychological effects of dispossession.

We’re fooling ourselves if we think that we can resolve the problems of colonisation without addressing the fundamental need to put people back on the land. That’s not simply a matter of dealing with the effects of colonisation, which we all agree need to be dealt with. You can’t let people suffer in that regard.

But we have to look at the fundamentals and we have to recognise that the disconnection from the land is more than just an economic deprivation. The disconnection from the land is more than just a political injustice. The disconnection from the land When native people are in that situation means they cannot be indigenous, they are prevented from living out the basic responsibilities of their nation in terms of their original teaching, and in terms of what it is to speak as an indigenous person.

Unless you are able to live out your culture and have the connection in your own homeland and to relate to that in a meaningful way, there is really no justice in the relationship at all. There’s really no justice in that person’s life.

To view this speech go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=VwJNy-B3IPA

Pingback: Weekly Wrap 20 January 2014 | pcbycp

Pingback: Assimilation 1 | pcbycp