This dispatch is from 11 July 2015

Hola,

I have a vague memory of going on a Boy Scouts outing. As I recall, my younger brother shot an arrow through the scout master’s cake as he was eating it, a sort of William Tell moment.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YIbYCOiETx0

That was to be our first and only Boy Scouts outing in Argentina. Some years later I went to the Boy Scouts in Australia, twice. On discovering that there was a trade in scout badges of merit, I decided that scouting wasn’t my cup of tea.

That first outing was in a forest, and I remember that up in the trees there were “claveles del aire” which made a lasting impression on me. I had always assumed that these were parasitic.

That first outing was in a forest, and I remember that up in the trees there were “claveles del aire” which made a lasting impression on me. I had always assumed that these were parasitic.

A friend alerted me to the existence of epiphytes. Wikipedia tells me an epiphyte is a plant that grows harmlessly upon another plant (such as a tree) and derives its moisture and nutrients from the air, rain, and sometimes from debris accumulating around it. Clavel del Aire is an epiphyte. Clavel is Spanish for carnation- ‘Aerial Carnation’. Ah!, the joys of Googling!.

Epiphytes are not parasites.

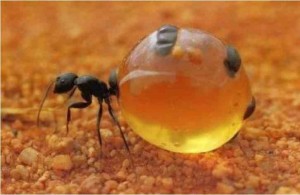

The most common tree around Yuendumu is manja (Mulga- Acacia aneura). Several species of mistletoe grow on mulga. Mistletoe is parasitic. Yungkurrmu is one such and has delicious sticky red and yellow berries. Another mistletoe that grows on mulga is ngardanykinyi. The ngardanykinyi-ngarnu bird has a symbiotic relationship with the parasite: it eats the berries and excretes the seeds onto other trees. On occasions, mistletoe will kill the host tree.  Mulga trees have a symbiotic relationship withants. The tree releases drops of fluid that contains sugar for the ants to eat, and in return the ants protect the trees against other predators by attacking them whenever the predators try to target the trees. One such ant species is the Yurrampi (Honey ant). They are even more delicious than the aforementioned berries, and don’t damage the tree.

Mulga trees have a symbiotic relationship withants. The tree releases drops of fluid that contains sugar for the ants to eat, and in return the ants protect the trees against other predators by attacking them whenever the predators try to target the trees. One such ant species is the Yurrampi (Honey ant). They are even more delicious than the aforementioned berries, and don’t damage the tree.

An incredible variety of plants grow under incredibly varied conditions. When young plants are transplanted to a new location, often their roots are damaged and the plants suffer and have to throw new roots to survive, which they don’t always do. Sometimes plants thrive in a new environment. The Monterrey pine (Pinus radiata) reaches a height of 30 meters in its native Mexico; in Australia it grows to 60 meters. I remember our family picking wild blackberries off small shrubs on the dunes near Zandvoort (Noord Holland), yet in Australia blackberries grow into impenetrable thickets that are often sprayed with poison in desperate attempts at controlling and eradicating them. They are a weed.

I’ve also been alerted to a body of research into what have been labeled Third Culture Kids (TCK). The Wikipedia entry for TCK finishes with a poem that explains the concept:

Colors

I grew up in a Yellow country

But my parents are Blue.

I’m Blue.

Or at least, that is what they told me.

But I play with the Yellows.

I went to school with the Yellows.

I spoke the Yellow language.

I even dressed and appeared to be Yellow.

Then I moved to the Blue land.

Now I go to school with the Blues.

I speak the Blue language.

I even dress and look Blue.

But deep down, inside me, something’s Yellow.

I love the Blue country.

But my ways are tinted with Yellow.

When I am in the Blue land,

I want to be Yellow.

When I am in the Yellow land,

I want to be Blue.

Why can’t I be both?

A place where I can be me.

A place where I can be green.

I just want to be green

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0O87fFRizZY

TCKs come in many combinations and permutations. Fifty shades of green if you like.

Most Australian Aborigines are TCKs, not least the stolen children.

Like plants they are incredibly varied and grow up under incredibly varied conditions. Often they are uprooted and placed in unsuitable environments in which they rarely thrive.

Research has shown that the most undisturbed and remote Aborigines are the healthiest (in body and mind).

The so called ‘Aboriginal Industry’ is like a blackberry thicket. In places like Yuendumu there are an ever increasing number of introduced non-TCKs (FIFOs). Yuendumu is getting to be like a field of buffel grass.

The so called ‘Aboriginal Industry’ is like a blackberry thicket. In places like Yuendumu there are an ever increasing number of introduced non-TCKs (FIFOs). Yuendumu is getting to be like a field of buffel grass.

Many of these FIFOs fancy themselves experts in Aboriginal Affairs.

Many are parasitic. They are slowly killing the very culture that sustains their host plant- the Aboriginal Industry.

My friend the TCK likes to think of himself as an epiphyte.

I’m also a TCK. I aspire to be symbiotic.

Just colour my world-

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MJhOsfzwDjY

Chau,

Frenk/Franklin/Frank/Jungarrayi