This piece was published by Elly Varenti on Facebook. It is beautiful, and a perfect testament to a life lived full.

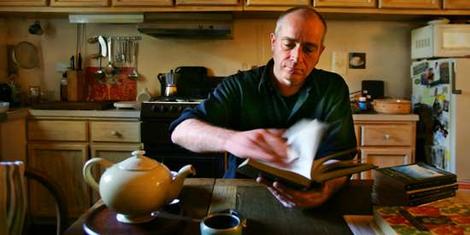

A best friend for over 30 years, Michael Gurr came to live in ‘my’ street in Castlemaine in regional Victoria 3 years ago. He loved the place. Occasionally I would protest its smallness, its arty-folksy-smallness and he would just look at me, proffer another piece of his onion tart or tea cake or some such other Moroccan or Mediterranean thing he had just made and say something like, ‘El, negative is easy, try positive, it’s harder.’ Or, ‘I hope you are not on some bloody nonsense diet again because I have made French custard poached pears.’

He loved to cook, to garden and, most recently, to walk home form town carrying big-ish new things for the house: an olde-worlde record player so that he could revisit his millions of Dylan albums. A large framed drawing/collage by a local artist – ’Take a closer look’, he said. ‘There’s more to it, the closer you get.’ Once I arrived at his place – a daily or double-daily visit usually -and he announced that he had bought 3 quail. ‘Yuk. I can’t eat quail,’ I said. ‘They are far too small and delicate and it just feels wrong somehow.’ ‘Not to eat,’ he said. ‘To admire. They are magnificent.’ And there they were outside the back screen door, all set up in their new little double storey hutch replete with straw matting, tiny pot plants and an ensuite bathing area.

His little weatherboard cottage opposite the footy oval was comfort and joy to him, poised as it was in perfect perving distance from the parade of locals on the way to the pub or train station or botanic gardens or pool in our street. He relished the crispy night footy training and Saturday matches – ‘I love the sound of it,’ he said. ‘It’s the sound of place and belonging.’ He always had something or other to give to my mother or me every time I left – The Guardian Weekly usually. My 85-year-old mother was always grateful – she loved him like a son and got cross with him like a son too – but she never was able to read those papers for the tininess of the print but never had the heart to tell him. Michael also gave her the latest political biography he had just devoured and once insisted she read one of his beloved Elizabeth David cook books. Mum was not interested in the cook books but took the other stuff happily. Last week it was a jar of pickled lemons. ‘They are not ready yet so don’t open them, just let them be for a while. Somethings do get better in time, you know.’ The pickled lemon philosopher sometimes gave me the shits. He could be opinionated and obstinate too. But kindness and largesse… Mate, he invented those words.

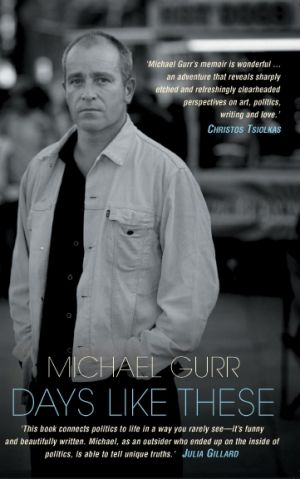

From the moment I met him when we were 21 and 22 respectively, I knew he was something out of the box: so smart, so funny, so generous, so wicked, so old-young, so singular, so confident without swagger, so unwittingly beautiful. The first time I saw one of his plays I experienced a sort of dwarfing awe. The second time I saw one of plays, I forgot it was a play, so immersed was I in his writing’s signature rhythms, the ideas layered and demanding, the wit, rude and shocking, the characters flawed and magnificently conflicted, and the politics searing and prescient.

We lived together for 5 years in our 20’s and they were, really, no nostalgia here because, ‘Nostalgia is a conservative impulse. A retreat into what seems knowable is dangerous,’ he reckons. They were 5 of the most creative, instructive, hilarious, vital and deliciously, domestically safe and exciting years of my life.

In recent months Michael became ill. He never complained, he never asked much of me or others, only for me to be kind of around and to sometimes drive him places because he had always refused, perversely, to ever get a bloody licence and walking even short distances had got hard for him. Our time together began to change, the balance to shift, as his fiercely resistant increasing dependence began to take centre stage.

I have never loved another person like I have loved this extraordinarily gifted (yes, an unfashionable word I know) man. His loyalty to his ‘tribe’, as he would say, was breath-taking, if not sometimes intractable and stubborn.

A true autodidact, Michael was learning up until 9 days before he died. ‘Did you know,’ he said to me while we sat in his favourite cafe atop the hill at the back of his house in the old gaol drinking black tea and eating apple slices. ‘I dreamt a new play last night. First time in ages. It’s called karaoke. Did you know, that I have been spelling the word kareoke wrong for years?’ And then I asked, as I have always asked every single time over the past 35 years even though I always get the same answer.’ What’s it about?’ And then he says, ‘I never talk about what I’m writing. Why would I? Once I speak it, then it no longer demands to be written.’

Michael’s work was his life, his life his work, his family his theatre, his friends his family, his sisters and brothers, his nieces and nephews, my son, his god children, his students, his former-partner of 23-years, his comrades, his colleagues, his actors, his pollys, his barber, his fish monger, his books, his newspapers, his quail and his cat were his life. His death feels like an amputation.

Who the fuck is going to call out my whingeing now? Who in hell do I give my miserable first drafts to for brutal but fair editing? Who do I now visit most days and wish to god he would stop smoking inside the house like it’s still the 1980s? Who do I care about and for, because he has always, always cared about, and for me? Who has my back now?