Here at Passive Complicity we are interested in ownership, in ‘Private Property’, in the Commons. Who owns the stories we tell? Are they really the property of the storyteller, or are they in some way shared by all those who have helped form them? Who owns the land we walk on, the land we have our houses on? When we look back was it ever really bought from the original inhabitants or expropriated in some ‘legalistic’ form, perhaps taken in exchange for beads, mirrors and trinkets in an exchange in which one party had no real idea what was going on? Who owns ideas, music, art, inventions? Hasn’t all society played a role in the all of these? Intellectual property, genes, seeds? And as important as any who owns the recipes we cook by?

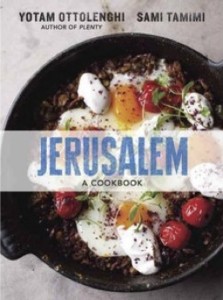

Sami Tamimi and Yotam Ottolenghi have written a wonderful book “Jerusalem, A Cookbook” 2012, (Random House, New York) in which they discuss this very question. Here are their thoughts.

Sami Tamimi and Yotam Ottolenghi have written a wonderful book “Jerusalem, A Cookbook” 2012, (Random House, New York) in which they discuss this very question. Here are their thoughts.

“In the part of the world we are dealing with everybody wants to won everything. Existence feels so uncertain and so fragile that people fight fiercely and with great passion to hold onto things: land, culture, religious symbols, food – everything is in danger of being snatched away or of disappearing. The result is fiery arguments about ownership, provenance, about who and what come first.

As we have seen through our investigations, and will become blatantly apparent to anyone reading and cooking from this book, these arguments are futile.

Firstly, they are futile because it doesn’t really matter. Looking back in time or far afield into distant lands is simply distracting. The beauty of food and of eating is that they are rooted in the now. Food is a basic hedonistic pleasure, a sensual instinct we all share and revel in. It is a shame to spoil it.

Secondly, you can always search further back in time. Hummus for example, a highly explosive subject, is undeniably a staple of the local Palestinian population, but it was also a permanent feature on dinner tables of Aleppine Jews who lived in Syria for millennia and then arrived in Jerusalem in the 1950’s and 1960’s. Who is more deserving of calling hummus their own? Neither. Nobody ‘owns’ a dish because it is very likely that someone else cooked it before them and another person before that.

Thirdly, and this is the most crucial point, in this soup of a city it is completely impossible to find who invented this delicacy and who brought that one with them. The food cultures are mashed and fused together in a way that is impossible to unravel. They interact all the time and influence one another constantly, so nothing is pure any more. In fact, nothing ever was. Jerusalem was never an isolated bastion. Over millennia it has seen countless immigrants, occupiers, visitors, and merchants – all bringing foods and recipes from the four corners of the earth.

As a result, as much as we try to attribute foods to nations, to ascertain the origin of a dish, we often end up discovering a dozen other dishes that are extremely similar, that work with the same ingredients and the same principles to make a final result that is just ever so slightly different, a variation on a theme.”