Last week we noted that Liam Jurrah was a victim of the NT Intervention (NTER). The Editor of Tracker magazine, Chris Graham explains Liam’s situation in this article first published in July 2012

Different world: understanding Indigenous justice

by Chris Graham

Less than a month ago, the Federal Government passed legislation extending the Northern Territory intervention for another 10 years. It barely rated a mention in the mainstream media.

But this week, Aboriginal people – and one in particular – are very much in the media spotlight.

Melbourne Demons star Liam Jurrah is currently appearing in an Alice Springs court, charged with assaulting his cousin, Basil Jurrah.

The circumstances of the alleged violence are part of a court proceeding, and getting plenty of play in other media. So I won’t revisit them here, save to say that Liam, Christopher Walker and Josiah Fry are alleged to have assaulted Basil Jurrah and at least four others in two incidents at the Little Sisters town camp in Alice Springs in March.

Prosecutors claim they led a 20-strong group because of tensions over the death of another Aboriginal man, Kumanjayi Watson, in 2010.

That death came about as a result of ‘payback gone wrong’, but that only partly explains the media interest, because the story ticks quite a few other mainstream boxes as well, including drunken Aboriginal violence and dysfunction, sport, and most importantly, celebrity.

Jurrah, in case you’ve been living under a rock, is a big deal in the AFL. His great skill aside, he’s the first Aboriginal man from a Central Deserts community to play in the big league. But the fact is that while AFL is as much a religion for blackfellas as it is for whitefellas, and while Liam Jurrah’s status as a player affords him a special respect among Aboriginal people in Central Australia, he could walk away from the AFL tomorrow and it would mean very little the average blackfella.

As good as he is at it, football is just something Liam Jurrah does. It doesn’t define him.

What does define him is the fact that he is a young Warlpiri man, a freshwater blackfella from the Central Deserts region. His skin name is Jungarrayi, his mother is Corrina, his father is Leo (also a great footballer) and his grandmother is Cecily. From the Warlpiri perspective, those are most of the things that really matter.

That and the fact that notwithstanding football stardom, Liam Jurrah is not excused from his cultural obligations, payback being one of them.

As brutal as it can sometimes be, the whole purpose of payback is to rule a line under an incident and allow people to move on. Sometimes payback goes wrong, although if you’re familiar with the number of deaths in custody – black or white – then you’d hardly suggest the white system of justice is flawless either.

I don’t excuse the death of Kumanjayi Watson – it should not have happened. But nor do I believe that Australians really understand how their justice system has impacted on this whole saga.

The man who killed Kumanjayi Watson was jailed. As a result, properly controlled and sanctioned payback never occurred. Much of the violence that we’ve seen in Yuendumu since has been a direct result of that. More payback. And then payback for payback. And on it goes.

The irony is that white people intervened in the belief they were doing the right thing. But the reality is we’ve made things a whole lot worse, and a whole lot more people have been hurt as a result.

It all harks back to the five most dangerous white words in Aboriginal affairs: ‘At least we’re doing something’.

It’s the ‘something’ that is the problem.

We can’t speculate on his reasons for the alleged assault, however if it is caught up with payback it is important to understand the obligations of Indigenous Australians to their kin.

Jurrah’s obligation to his kin is something very foreign to most non-Aboriginal Australians. I have an obligation to ring my mum on her birthday. I have an obligation to turn up to annual family events, weddings, funerals etc. In Liam Jurrah’s world, his family obligation is the whole reason for his existence. It’s at the core of Aboriginal being, and there are very good historical reasons for that.

You don’t survive and thrive for 60,000 years in one of the harshest environments on earth if your countrymen don’t understand their obligations. You don’t feel like hunting this week? People starve. That’s just one of the many reasons why the fabric of Aboriginal society is built on obligation.

To get your head around obligation and the Warlpiri perspective, you need to understand how Warlpiri (and Aboriginal people from Redfern to Ramingining) think.

What is important to them is not necessarily what is important to us. Like the elderly.

As white Australians, we have a tendency to stick our old people in a nursing home. Aboriginal people, by contrast, prefer to have their elders not only live out their years with their family, but actually lead their clans until their passing.

The irony is that Australians often lament our treatment of the elderly. Aboriginal people got it right a long time ago.

Sharing is another good example. Aboriginal people share everything because it makes good sense and again, there’s good historical reasons for it. You might have something to share today, but if you refuse, then tomorrow when you have nothing, you get nothing. That’s a feature of poverty as much as it is of Aboriginality, but regardless, it makes sense when you think about it.

Of course, we call Aboriginal sharing ‘humbugging’. So do many Aboriginal people, and it can often lead to problems. But it can also lead to solutions.

Many ancient virtues of Aboriginal culture are these today considered by white people to be modern flaws. But the gap in understanding is not just about the way Aboriginal people live, it’s also about the things Aboriginal people value.

Ochre is used by Aboriginal people in ceremonies and in art. It is, and always has been, an extremely valuable commodity. The Warlpiri ochre mine, for example, is a sacred place and is still used today. But to most white people ochre is just dirt. It has no real value or purpose.

If you flip it around, white people believe gold is extremely valuable. It can be mined and sold for a profit. Nations have prospered, and whole economies built on the rush for gold. To Aboriginal people, it’s a bit of rock in the ground. It has no real value or purpose.

Neither is right or wrong, they’re just different perspectives.

Another example is ceremony. Aboriginal people today still place great enormous importance on the ceremonies they’ve practiced for tens of thousands of years. Why? Because it has helped to sustain them. Ceremony is where law and history are passed on to the young. It makes Aboriginal people feel connected to each other. But to many white people, it’s just a group of blackfellas dancing around in the dirt.

Switch it around and many non-Aboriginal Australians believe one of their most sacred ceremonies is Anzac Day. Why? Because it pays homage to people who sacrificed so much to ensure we enjoy a free and privileged life today. But to many Aboriginal people, it’s just another day in April. They have their own warriors and their own wars, most of them waged against us (although we rarely acknowledge them).

The fact is, blackfellas at Yuendumu or anywhere else are not simply going to abandon their beliefs or world views because whitefellas think they’re weird, anymore than blackfellas expect whitefellas will abandon theirs.

Celebrating Liam Jurrah as a footballer is a good thing, because he’s a great player, but if we want to also celebrate him for who he is – an Aboriginal man with a vibrant, important and complex culture – then we have to start at least trying to understand his perspective, and that of his people.

And that’s the point. When you strip it all back – when you take out all the politics and the history – one of the main problems between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Australians is a massive gap in understanding.

Aboriginal people like dirt. We like rocks.

The differences are by no means insurmountable, but I don’t see a hell of a lot of effort on the part of white Australia to bridge the gap.

And that’s why Liam Jurrah’s story – his life story, not the story around the violence at the Little Sisters town camp – is the REAL story, because it affords white Australia an opportunity to better understand the Aboriginal perspective.

That opportunity, however, will be missed if we don’t demand that our media – and our governments – look beyond the violence and the celebrity, and find out what is really going on.

If you’re interested to look, a great place to start is in legislation like Stronger Futures, the very same thing our media are ignoring and our politicians are passing.

One of its provisions is to supplant Aboriginal law with white law, precisely one of the things that got us in this mess in the first place.

Chris Graham is the managing editor of Tracker magazine, and a Walkley Award and human rights award winning writer. View his full profile here.

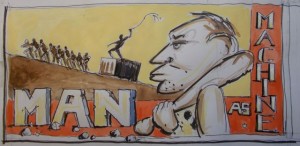

For Property values and ease of business.

For Property values and ease of business. The street frontage and sides devoted to ramps, air conditioning ducts, grills, vents and concrete. Zero connection to the street, or to the town. We learnt that behind the towering crystalline steel and glass facade, office workers plied their trade, in triplicate, white, pink and yellow forms to their respective trays.

The street frontage and sides devoted to ramps, air conditioning ducts, grills, vents and concrete. Zero connection to the street, or to the town. We learnt that behind the towering crystalline steel and glass facade, office workers plied their trade, in triplicate, white, pink and yellow forms to their respective trays.