A passively complicit society unquestioningly accepts the authority of government. The Australian Government is reinforcing its authority. Here we reprint a significant article on the subject.

Brandis ties NGO funding to non-advocacy

The Abbott government is using money and law to close down criticism and gag the community’s most trusted voices.

There was something missing from the revised service agreements under which the federal government provides funding to community legal centres around Australia, recently sent out to 140-odd such organisations.

The old clause five was gone. That was the one that began: “The Commonwealth is committed to ensuring that its agreements do not contain provisions that could be used to stifle legitimate debate or prevent organisations engaging in advocacy activities.”

The old clause five went on to stress that: “[N]o right or obligation arising under this Agreement will be read or understood by the Commonwealth as limiting the Organisation’s right to enter into public debate or criticism of the Commonwealth, its agencies, employees, servants or agents.”

It also stipulated that there was no obligation to obtain any advance approval from the government before going public with any criticism.

But when the Abbott government’s revised agreements went to the organisations in mid-June, all of that was gone. Instead, the new conditions, which came into force on July 1, specifically state that organisations cannot use Commonwealth money for any activity directed towards law reform or advocacy.

Not surprisingly, the sector sees this as a retrograde step. So do the Labor Party, which inserted clause five into the agreements, the Greens and the majority of state governments.

The Productivity Commission, in its recent interim Access to Justice report, found advocacy was actually an efficient use of resources. That’s because it addressed systemic issues rather than just individual cases. Thus “by clarifying the law it can also benefit the community more broadly”.

Shadow Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus, QC, agrees. “CLCs and legal aid commissions are best placed, from their work, to observe when reform might aid not just their immediate clients, but thousands of others in the community.”

Reform through advocacy

Even Attorney-General George Brandis, QC, under sharp questioning from Greens senator Penny Wright in a senate estimates committee in May, said he “did not dispute” that advocacy “may be a useful thing … may be a desirable thing”.

Given the tight budgetary circumstances, however, the “frontline services” of representing clients had to take priority, he said. And that’s why the government was moving to ensure its money was not used for advocacy.

Few people close to the issue believe Brandis was giving a straight answer.

“The government was saying they would not be cutting frontline services, only policy and advocacy work,” says Michael Smith, convenor of the National Association of Community Legal Centres.

“They then cut about $8 million, or about 20 per cent, out of community legal services, and most of that comes out of frontline services. They are using the policy and advocacy line as a way of justifying these cuts.”

HOWARD LED THE WAY

The Abbott government is following the course set by the Howard government, which was dogged in its efforts to ensure the non-profit sector was prevented from voicing unwelcome opinions. Contracts with community sector organisations routinely included gag clauses and reserved the right to censor public statements before they were released.

After Howard lost the 2007 election, the incoming Labor government immediately began rewriting thousands of contracts with the non-profit sector, removing the gag. But it was only in its dying months, in May 2013, that the previous government managed to put this independence into legislation, through the non-profit sector freedom to advocate bill.

Nonetheless, the gags are coming back, if in somewhat modified form. While the government cannot – because of that legislation – completely prevent advocacy by community law centres, it can insist that no money it provides is used for the purpose. If these groups want to advocate, they can fund it with money from other sources, or do it, as Brandis suggested in estimates, in their spare time.

Gag clauses, though, are just one means by which the government can seek to stifle advocacy.

“There is any number of ways, if the activities of a charity are inconvenient to the government of the day, that they can make it difficult for those charities,” says Elizabeth McKinnon, a lawyer for the Australian Conservation Foundation.

Using the tax authorities to go after them, for example. She and others in the non-profit sector look worriedly to the situation in Canada, where Tony Abbott’s ideological soul mate, Prime Minister Stephen Harper, in 2012 ordered the Canada Revenue Agency to audit a large number of charities, with the threat of action including the removal of the charitable status of those deemed to be diverting too much of their resources to “political” activity.

Environment groups appear to have been the main target, although a wide range of other organisations, working in the areas of animal welfare, education, health, human rights and even poverty alleviation, have been subject to audit. The process has had a predictably chilling effect on charitable advocacy.

Back in the latter days of the Howard government, the tax office moved to revoke the charitable status of AidWatch, an organisation that researches, monitors and, importantly, campaigns to generate public debate about the effectiveness of foreign aid.

The commissioner’s reasons for going after AidWatch were essentially that it did not itself distribute aid and thus was not charitable, and, second, its objective of generating public debate amounted to a political purpose.

It went all the way to the High Court, where the tax office lost. AidWatch’s activities were deemed legitimately charitable in that it was acting in pursuit of a public good.

Government uses ATO and Federal Court

Subsequently the Labor government put up legislation defining charities and the purposes of non-profits that could be deemed charitable.

“When we worked on the new definition of charity, we actually had the AidWatch case written into the explanatory memorandum of the bill, because if it was ever legally questioned, there was a listed example from the court,” says David Crosbie, the Community Council for Australia’s chief executive. “So the new definition of charity, which came into force January 1 this year, was that if you were involved in advocacy, provided you were not a political organisation, and the advocacy benefited your purpose, you were fully entitled to engage.”

That has not stopped the tax office trying again.

“The most recent case was in the [Federal] court a couple of weeks ago, relating to the Hunger Project,” says Crosbie.

“They said it wasn’t a charity because it didn’t provide direct services. The Hunger Project raises money to support other charitable projects aimed at reducing hunger overseas. The ATO lost that case, just as they lost the AidWatch case.”

The most recent Australian Bureau of Statistics data show that at the end of last year, there were about 58,000 active non-profit organisations around the country, employing about 1.1 million people, turning over more than $107 billion, and growing at a rate of about

8 per cent a year.

Of those, the majority – about 45,000 – have “deductible gift recipient” status, meaning people can claim donations against their taxes. And these organisations also get exemption from other taxes, such as fringe benefits tax.

So it’s not hard to see why the tax office would be gunning for charities: they represent a very large and very fast-growing leakage of revenue. Nor is it hard to see why a cash-strapped government would be concerned, even absent ideological considerations.

Targetting refugee and environmental groups

But, of course, there are ideological considerations.

Only a couple of weeks ago, at a meeting of the Liberal Party’s federal council, MP Andrew Nikolic moved that “eco charities be treated as corporations under consumer and competition law” and “should not be eligible for deductible gift recipient status when advocating political issues”.

The motion passed unanimously.

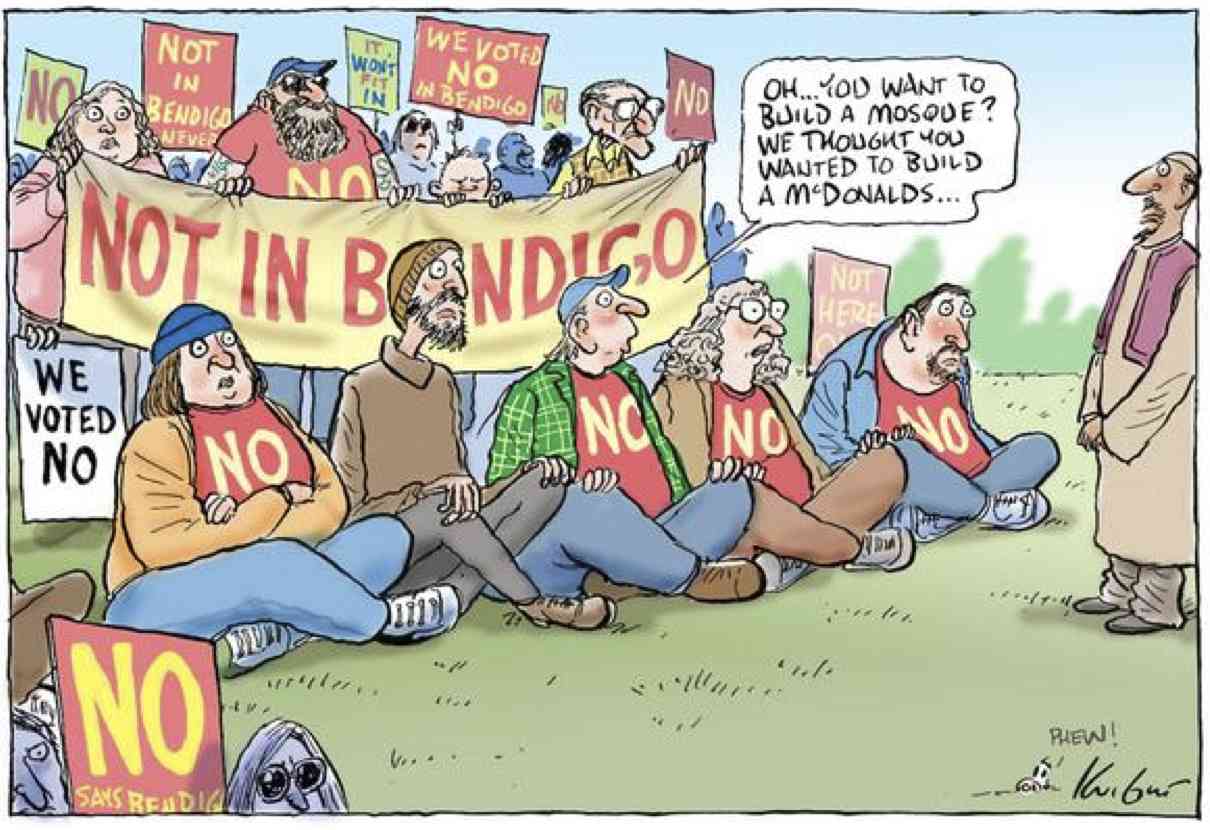

And while Nikolic’s resolution targeted green charities in particular, there is no doubt the government is working assiduously to shut down inconvenient advocacy wherever possible.

Just a couple of weeks after this year’s budget, Immigration Minister Scott Morrison cut off funds to the Refugee Council of Australia, saying the government did not think “taxpayer funding should be there to support what is effectively an advocacy group”.

A number of other outspoken organisations in a range of areas also lost funding in the budget.

At least the community legal centres still have some money, albeit reduced and with strings attached. The state Environmental Defenders Offices don’t.

“Environmental Defenders have generally lost all of their federal money and some have also in some cases lost state money,” says Smith, whose organisation also covers EDOs.

Some have found other ways of getting resources, essentially by crowdfunding. “Some of the smaller ones may struggle for resources,” Smith says. “But I don’t think it will shut them up. The government may yet find them to be stronger advocates against elements of government policy than they used to be.”

Charities Commission under fire

The Coalition parties never supported the charities act, and initially wanted to repeal it, as well as abolish the new body set up to administer it, the Australian Charities and Not-for-Profits Commission.

“They seem to have gone very quiet about repealing the act,” says Ann O’Connell, a tax expert from the Not-for-Profit Project at Melbourne Law School. She suggests that is because the government has now “become aware” that the court decisions on charitable status would hold up, even if the act was gone.

But the government remains committed to getting rid of the commission, even though the commission is overwhelmingly supported by the sector. In its place, the Abbott government would give responsibility to the tax office.

“What we are seeing,” says David Ritter, the chief executive of Greenpeace Australia, “is a government pursuing everything it can think of in an agenda to control and silence civil society. And that should be of concern to all Australians.”

Defunding it, gag-clausing it, threatening its tax-deductibility. And potentially, says Ritter, criminalising it.

He refers to the Competition Policy Review, now being headed by former businessman Maurice Newman, not a noted friend of the environment.

A number of members want to change the secondary boycott provisions of the competition and consumer act, which currently exempt actions by consumer and environment groups.

If that were to happen, organisations would be breaking the law if they advocated that consumers avoid using certain products. They could not advocate boycotts, for example, of unsustainable fisheries, palm oil products from plantations where rainforest had been knocked down, or paper products produced from old-growth forests.

The review is due to be complete before the end of the year.

Would the government go so far as to actually criminalise advocacy? A broad coalition of environment, welfare and other groups is taking the threat very seriously and is now lobbying furiously.

Yet not only are these organisations – community legal centres, environmental defenders and other non-profits – often the most publicly trusted critics of government policy, they are frequently sought out by government for their expertise.

“I can’t tell you how often governments have come to us over the years seeking our involvement in policy work, or advice on improving their practices,” says Michael Smith. “Now, we’re not supposed to be having those conversations.”

Not under this government. No criticism allowed.