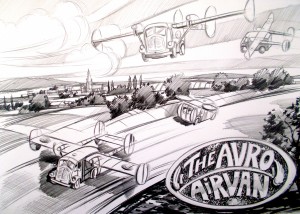

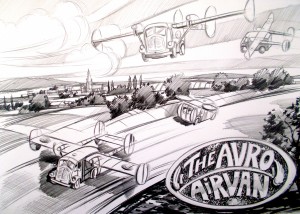

Airvans. Midlands C. 1950. A typical highway scene of Flying AirVans’ and Airvan in traffic mode. Note Collapsible boom and wings.

The Airvan was a masterpiece of immediate postwar design.

The first ever road-air hybrid. The basic body consisted of a standard Morris J type van. Simple, robust construction, and for road use possessed the standard reliable Morris 1500 straight four developing a comfortable 50 bhp. The air frame consisted of two retractable booms and a single tailplane, all of which could be retracted alongside the body of the van when motoring. The wings were simple lightweight spars of plywood with fabric control surfaces. The engine unit, the reliable and proven Gypsy inline four, then in use on the Tiger Moth. Air speed was a respectable 120 mph, with a surface ceiling of 10,000 feet. Over seventy were ordered by the Royal Mail for deliveries to remote locations and the fleet provided trouble free and reliable service for some twenty years until replaced by standard road delivery vehicles.

Morris Airvan Workers. All female fabricators at work on assembling boom tail section mountings.

The Avro Airvan was the only aircraft to be unveiled at both a motor show and an air show. This distinction established considerable publicity for the joint venture between AV Roe, makers of the famous Lancaster and Morris Motors. In spite of their bulky shape they were impressively agile in a fly past before his Majesty the King at Farnborough in 1947. So impressed were the Australian delegation to the Earls Court motorshow, the then Chifley government ordered fifty and had them shipped to Australia. In the United Kingdom the Airvan provided both economy and agility. Used principally as a short hop mail delivery service to the Channel Islands it provided a reliable, relatively economical service in areas that were; ‘best left geographically and socially isolated from the mainstream’. In Australia, the story was different. Originally purchased by the army, the Airvan was intended to provide close support and delivery of mail and services to far flung detachments of the Australian Army in places as remote as Norfolk Island, Port Headland, Charters Towers and Marble Bar. In this capacity the Airvan proved up to the task. A tropicalised version was adapted in late 1949, and provided a service between Cape York and the Thursday Islands.

Atomic Energy Commission Officers Maralinga 1956. Clearing land of Natives prior to testing. Captain L. Wilcox RAR sampling radioactive thermos.

However in early 1952 the then Federal Atomic Energy Commission concerned by Australias flagging nuclear industry decided to use the Airvan in the delivery of components from Adelaide to the new testing range at Maralinga and Woomera. For a short period the Air van proved eminently capable, being able to land in remote locations and motor over desert wastes to deliver vital components. In many cases outperforming the then standard utility vehicle the Land Rover series 1. On February 22nd, (Black Tuesday) disaster struck. The entire complement of Airvans’ were requisitioned to supply nuclear warheads, detonators and technical equipment to the Maralinga test site. Previous reconnisance had suggested a flat expanse of stony desert adjacent ground zero and the Airvans, flying in squadron formation, prepared to land. Unexpectedly, a dust storm, (which is quite prevalent in these parts) blew up, and the Airvans’ under orders and strictest secrecy, maintained wireless silence and descended into the sandy maelstrom. Unbeknown to the squadron, this area is now referred to as the Great Sandy Depression, plagued by quick sand, depressive tendencies and deceptively hard, (but soft underneath) salt pans.

The entire squadron upon landing, were consumed within minutes, with no trace left on the surface. Only by accident the relics were discovered recently by a survey team from Hancock prospecting.

Dejected leader of Hancock Propsecting Airvan retrieval expedition, Cmmdr T. Polkinghorne, (retd) upon finding no trace of Airvan Squadron.

Faced with the prospect of unearthing live ammunition and the potential for a catastrophic nuclear incident. The CEO of Hancock’s, Ms. Gina Rinehardt made a site inspection and tragically due to her weight, (roughly equivalent to an Airvan) became engulfed by the sands that had so fatefully consumed the Airvans’. A subsequent enquiry determined that the search was fruitless as the CEO was probably irradiated, and besides if alive and disinterred, would still be; ‘best left, geographically and socially isolated from the mainstream’.